Despite being more than 10 years old, Rich Communication Services, or RCS, will finally come of age in 2019. RCS is the GSMA-backed messaging successor to SMS, enabling new features like group chat, read receipts, is-typing indicators, and media file sharing.

Historically, RCS has been maligned by critics as being “too little, too late” and something that could never keep up with the feature-rich OTT messaging applications like Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, and Line.

It was anchored by standards bodies and its reliance on IMS, the IP Multimedia Subsystem, a complex [and expensive] architecture used for the signaling, policy management, billing, and transport of IP-based telecom services like Voice-over-LTE (VoLTE).

Even with the aforementioned stigmas, RCS survived, and in early 2017 it started gaining more widespread momentum. That’s when Google announced their decision to back RCS as the technology behind the default messaging application on Android devices. This would require them to work with the mobile network operators whose networks would be used for message routing and delivery, which they’ve done. Fast forward to present day, while still dealing with some fragmentation, the new RCS ecosystem is taking shape – but why?

First, to understand why RCS is happening today, it makes sense to look at some of the reasons why it failed to fully materialize in the past. In 2012, when RCS was first commercially available with any scale, there were a number of barriers that had to be overcome by the network operators. Unlike SMS, RCS didn’t have a native device client so operators had to procure their own clients and either work with OEMs to have them pre-installed or request that subscribers download an RCS app to choose and use over their native messaging client. Many operators were planning on rolling out their LTE networks but had yet to explore IMS, a key enabler for VoLTE, and a requirement for RCS. Furthermore, an updated person-to-person (P2P) messaging experience was not enough to justify the capital expense of deploying IMS, especially given that messaging revenues had already started to decline. The decline was not as severe in North America where unlimited messaging bundles were the norm. However, operators in Europe and other parts of the world where per-message tariffs were common were hemorrhaging revenue as the mass exodus to free OTT players like WhatsApp was in full swing. This was a harsh lesson. Operators were clinging to the idea that consumers cared about the phone number and its ubiquity. In reality, the minor inconvenience of joining an OTT community and getting your friends to join was not enough to deter people from free messaging. In summary, RCS had a multitude of forces working against it, with the most significant one being that it was seen as a cost center, not a revenue center. In regions where mobile was on the cusp of full market penetration, the only way to grow the bottom line besides stealing customers from the competition was to deploy new, revenue generating services or finding ways to cut costs, and RCS did neither.

Fast forwarding to 2017, what changed to make Google (and recently device giant Samsung) get involved in RCS, the GSMA to rekindle their industry push for RCS, and for operators to start road mapping their RCS deployments? Simply stated, changes in user behavior and the goals for RCS shifted the technology from a cost center to a revenue center. Looking at how user behavior has changed from 2012 to present day, consumers’ digital time has migrated from their desktops to a variety of apps on their mobile devices. But then app fatigue set in and the number of apps downloaded per month per user began to decline. Ultimately, a few mobile apps became responsible for consuming the majority of users’ digital time – social and messaging apps. This trend did not go unnoticed by the brand community, who will always choose to place their content (and marketing budgets) in the best position to get in front of the most consumers.

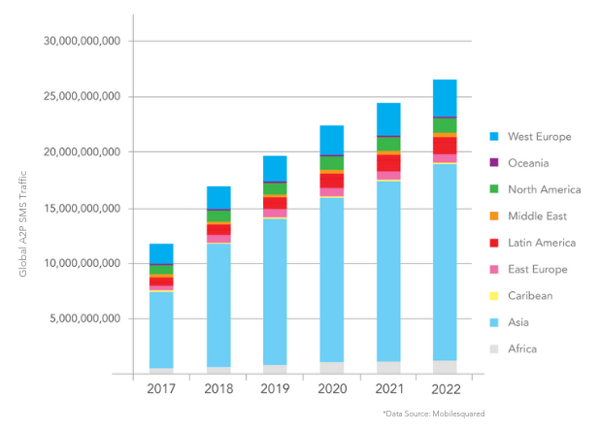

This trend towards messaging applications, being where customers reside and interact the most, has tremendously affected the goal and execution for RCS. The main objective was no longer to have a user experience strictly targeted at P2P messaging that was comparable to the OTTs - that ship had sailed. Having a me-too messaging app is surely not a compelling enough reason for subscribers to migrate back to operator-furnished messaging from free OTT apps. However, having an app-like experience where mobile subscribers can engage and interact with brands is compelling. Clearly, the OTT providers have realized this as well, so why does RCS stand a chance? First, consumers have a level of trust with their mobile operator that they don’t have with OTT players. OTT is free and consumers aren’t naïve as to why – because their behavioral data is the currency that pays for the service. Secondly, consumers clearly don’t have an aversion to using operator-supplied SMS for application-to-person (A2P) and person-to-application (P2A) messaging. While P2P SMS messaging has seen significant declines for years due to OTT attrition, global A2P SMS traffic is forecasted to see a CAGR of 10.8%, rising from 1.67 trillion in 2017 to 2.8 trillion in 2022[1]. And brands have come to realize that native messaging, with the ubiquity of a phone number, is still the most reliable way to reach a customer. For these reasons, major brands have expressed enthusiasm for RCS as a channel for richer customer engagement.

In addition to the user behavior trends, there have been a number of technical enablers that have evolved since 2012 that reinforce the case for RCS messaging-as-a-platform, or MaaP. Advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Natural Language Processing (NLP), are making automated conversations more human-like and smarter. This has led to the adoption of RCS and other interfaces for conversational commerce and customer support applications through chatbots, which can drive revenue and reduce costs for the enterprise/operator community.

In addition to the user behavior trends, there have been a number of technical enablers that have evolved since 2012 that reinforce the case for RCS messaging-as-a-platform, or MaaP. Advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Natural Language Processing (NLP), are making automated conversations more human-like and smarter. This has led to the adoption of RCS and other interfaces for conversational commerce and customer support applications through chatbots, which can drive revenue and reduce costs for the enterprise/operator community.

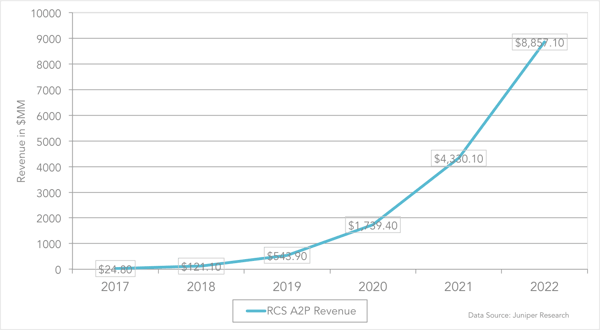

RCS’s shift from a cost center to a revenue center is at the heart of its resurgence. In fact, Juniper Research predicts that the A2P RCS revenue opportunity for operators will reach $8.8 billion in 2022, rising from $121 million in 2018[2].

This shift has led the mobile operator community, with the backing of device industry giants like Google and Samsung, to knock down the barriers that stood in its way back in 2012. Google and Samsung are committed to delivering devices that have RCS-enabled clients pre-installed on Android devices, eliminating the burden that had once been left to the operator. Beyond ensuring a native messaging experience for the subscriber, this commitment reduces the fragmentation and interoperability nightmares that went with having an array of 3rd party clients in circulation. With many regions having already completed their LTE deployments, they’ve moved on to deploying VoLTE, and the requisite IMS core networks, which will optimize their networks and enable them to re-farm their high-value 2G/3G spectrum. In these cases, RCS doesn’t need to be used as the justification for IMS deployment as it did in 2012. However, for those operators who have yet to deploy VoLTE or IMS, the value of RCS and its monetization opportunities has become a factor in their strategic network planning. Lastly, from a P2P perspective, RCS Hubs are now being deployed to ensure that subscribers on different networks can communicate with each other using the richer RCS mobile experience.

2018 has been a year of enablement across the entire ecosystem, with leading operators globally deploying RCS infrastructure, interconnect hubs emerging, content aggregators getting network connectivity, and brands creating their first RCS campaigns. In 2019, continued deployments and the corresponding subscriber counts will cross the reach threshold that brands have been waiting for to jump in with both feet, creating a rich environment for subscribers, strengthening the subscriber-operator relationship, and putting the mobile operator back in the center of the mobile value chain.

[1] Global A2P SMS Messaging Forecast Data by Country 2017-2022 Databook, Mobilesquared

[2] Mobile Messaging Deep Dive Data & Forecasting 2018-2022, Juniper Research